When Ebola struck Sierra Leone in 2014, its terror lay in its mystery. It was a gruesome disease that no one had seen before, and claimed lives without apparent cause or cure. But Mohamed Moray had a broader perspective.

“It was just like the war,” he says, referring to the civil conflict of the 1990s, in which an estimated 50,000 people were killed or had limbs hacked off by rebel fighters.

Now, as then, communities were splintering under the twin pressures of fear and suspicion; amid the chaos, few had the chance to mourn properly for those whom they had lost.

Moray knew exactly what that dangerous alchemy of fear and grief could spawn – anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder – because he had watched it happended before

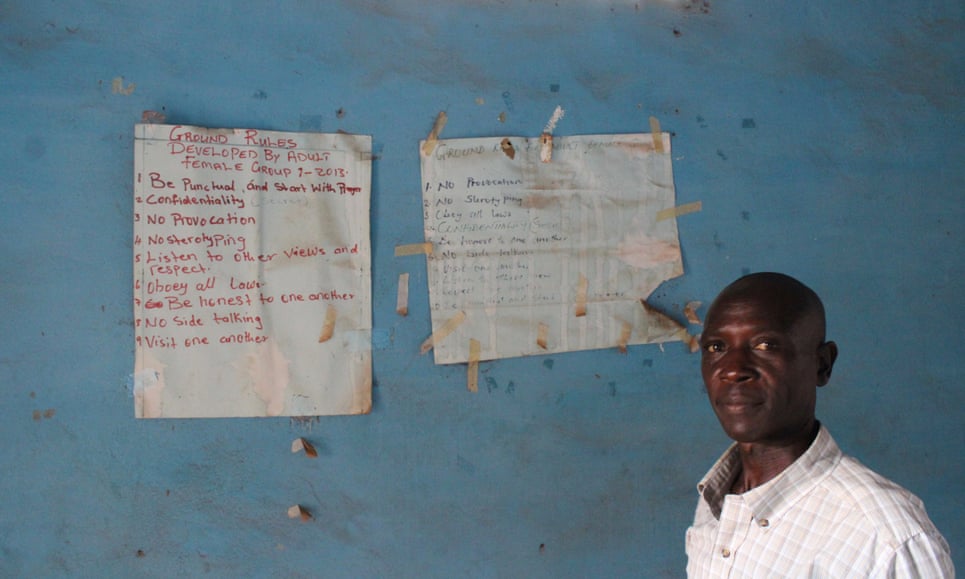

man who knows how to swim cannot watch his friend drown without feeling great stress,” says Moray, clinical supervisor for the regional branch of the Community Association for Psychosocial Services (Caps), which has provided counselling to communities around Kailahun in eastern Sierra Leone since the end of the war. “So when we saw this happen again, we felt a responsibility to do something.”

For nearly two years, Ebola stormed across this corner of west Africa, devastating communities and health systems that were already among the world’s poorest. But within that public health emergency was a second crisis, acute but nearly invisible: one of mental healthcare.

When Ebola hit, just 136 doctors were working in the public sector in Sierra Leone, a huge shortfall for a population of roughly 7 million people. But there was also just one active psychiatrist, a wry 70-year-old who spent his mornings scribbling prescriptions at the country’s only psychiatric hospital in the Kissy neighbourhood of eastern Freetown.

At this institution, which is also the oldest on the continent, most patients are kept chained. Treatment consists of little more than a daily dose of expired antipsychotic medication.

To Moray and his team, this state of affairs was frustrating, though hardly inexplicable: in the years during and just after the civil war, they had watched as money and expertise poured into the country in an effort to help mend emotional wounds.

A series of initiatives promised community healing, psychosocial support and empowerment. The confessional bonfires of one such project – which brought perpetrators and victims together in public pleas for forgiveness – even featured in the acclaimed documentary film Fambul Tok.

Moray and his fellow counsellors had started out as clients – and later employees – of the Center for Victims of Torture (CVT), an international NGO that provided counselling to Sierra Leonean refugees in Guinea in the 1990s and early 2000s. For several years, they criss-crossed Guinea, and later Sierra Leone, providing trauma counselling to those who needed help, as they once had.

No comments:

Post a Comment